“Children don’t lie. Slap them in the face and they tell you what they know,” Sameh*, a night watchman, says. The 18 year old was on night shift at Maowwiya elementary school north of Attatra’s Salateen street, Beit Lahiya, when the Israeli land invasion began.

Three days after the 18 January 2009 ceasefire, still shaken from his experience, Sameh recounted how the Israelis occupied the school and used it as a prison and interrogation centre, before bombing it. A year later, the blast holes still gape through the school’s walls and the missing floor has not been replaced.

“It was around 8am, January 4th, the first morning of the ground invasion. Israeli tanks came to the school. I started to run but the Israeli soldiers ordered me to stop. They pointed their guns at me and told me to take off my clothes.”

His voice trembles and face crumbles as he relives the pain and fear of his experience.

“They kept me for two days, didn’t let me dress during that time, didn’t give me food or water, and kept interrogating me, telling me to work with them, collaborate. I refused.”

At the same time, says Sameh, Israeli soldiers abducted another approximately 70 men from the area and held them captive in different classrooms.

“They took children prisoner too,” says Sameh. “The Israelis would question the children, slap them in the face, and question them again. They’d ask things like “where do you live? Where are the resistance?”

Mahmoud Al Qanouah, 23, stands near Sameh, nodding grimly in to his testimony.

“They brought me here too, held me for one day,” says the engineering graduate.

“But our troubles began at home,” he adds, pointing across the road to a 2 storey house ravaged with bullet and shelling holes.

The land beside the home, formerly an orange grove, is a churned mess of soil and tree stumps.

“We used to have many orange trees, as well as sheep, chickens and rabbits,” says Qanouah, walking past the razed trees. “All that was destroyed. We’ve got no source of income or food now.”

The street-facing wall gapes with a large, charred, missile hole. The entire first floor is smoky black, inhospitable.

“There were tanks around the house,” Qanouah remembers. “From 8:30 am until 11:30 that night they were shooting at the house and all over.

“We went downstairs, thinking it was safer. We felt a crash and realized a bulldozer had rammed the house.

Bassam Qanouah, 40, Mahmoud’s elder brother, continues the account.

“My wife, Ibtisam, and our mother went outside together, carrying a white cloth like a flag, waving it. They wanted the soldiers to know that we were unarmed and needed to escape the danger. An Israeli sniper occupying a neighbouring house shot my wife in the heart.”

Just outside the back door, next to strewn razed olive branches, Bassam Qanouah points to the place where Ibtisam fell.

“She died immediately.”

The horror continued as the remaining family members stayed trapped inside while the Israeli bulldozer resumed ramming their home.

“It was ramming the support pillars of the house,” says Mahmoud.

They heard the Israeli soldiers knocking on the door. “Bassam went to answer it, but the Israelis shot up and down the length of the door. He couldn’t open it. They kept hammering on the door.”

“We have small children, we have small children,” Bassam says he yelled in Hebrew.

The soldiers’ response was to shoot 5 bullets in the direction of his voice. He turns and points to a shattered mirror and holes in the wall behind which the family were cowering.

“The Israeli soldiers came in and ordered us all to take off our clothes,” says Mahmoud. “In front of the women,” he adds, a point of great shame.

At the time, he explains, his family and neighbours –including 8 men and 24 women and children –were weathering the Israeli assault together in the house.

“We were kept captive by the Israeli soldiers for the first day. The second day they took all the males to the elementary school across the street.”

At the school, the men were held with other men from the area, as Saleh testified. They were interrogated, some beaten, and denied food and water, says Mahmoud Qanouah.

“The second day, they took our group back to home, asked for our ID cards,” says Qanouah.

But the IOF took Amer and another man in tanks to Ashkelon where Amer says they were held outdoors blindfolded and handcuffed behind their backs for 3 days, without food and water, interrogated and beaten so badly he couldn’t speak for 2 days.

His is another story in itself, one repeated throughout Gaza during Israel’s massacre.

“Israeli soldiers told the rest of my family to walk to Jabaliya,” says Mahmoud. “We tried to take Ibtisam’s body with us.”

“They told us it was safe to walk, but as we walked they shelled the road we were walking on. My mother was wounded with shrapnel to her hip and I got shrapnel in my head. We dropped Ibtisam’s body and continued to walk, all the way to Kamal Adwan hospital, at least half an hour of walking. An Apache flew above us, following us.”

For the next 2 days, the family was unable to retrieve Ibtisam’s body. Nor could the Red Cross, Red Crescent, or Civil Defence, retrieve it due to the shelling and shooting from Israeli soldiers still occupying the area.

After the worst of the bombardment had finished, the Qanouahs returned to their home, shelled, shot-up and ransacked by the Israeli soldiers who occupied it during the rest of the invasion.

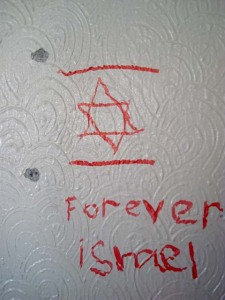

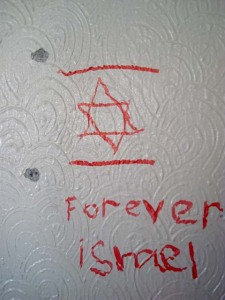

Like in Ezbet Abed Rabbo and other areas where soldiers had occupied houses, the IOF had bored sniper holes in most of the walls. Spent bullet casings littered the balconies where soldiers shot from behind sandbags. And the IOF graffiti stained walls throughout the home.

“They stole over $2000 from our house, and our cell phones” says Mahmoud Qanouah. “There’s no way to report this, no compensation. And they destroyed our car –we used it as a taxi. How can we get a new one? How can we earn a living?”

The house next to Qanouah’s was completely destroyed, rendered unliveable.

“My two uncles’ families –11 people—are living upstairs now. Now there’re 9 of us living on this floor: my brothers, father, sister, wife and I.”

As life goes on in Gaza one year later, people resume the struggle to work and live with, yearning for the most basic of rights.

“I got married 2 months ago. We’re trying to continue with our lives… but still I don’t have work. I’m trained as an engineer, but there’s no work in Gaza. No one in my family works. We survive off of food aid given every 40 days: ½ kilo of flour, oil, 2 kilos sugar.”

“We don’t want to leave and forget Gaza. But if the borders were open, we’d have work.

Many in Gaza feel another Israeli war looms. Most felt that immediately following the halt of the last major attacks.

“Sure Israel can wage a new war on us at any time. We expect that. Israel doesn’t care about international law or what the world thinks. But we are strong, resilient people, Palestinians. We will stay here, die here.”

*

IOF graffiti in Qanouah house

*gracious, after everything